John William Hall

John William Hall

John William Hall was born on the 13th of February 1892 in the village of Riby in Lincolnshire. His parents were Elizabeth (née Keal) and Richard Hall.

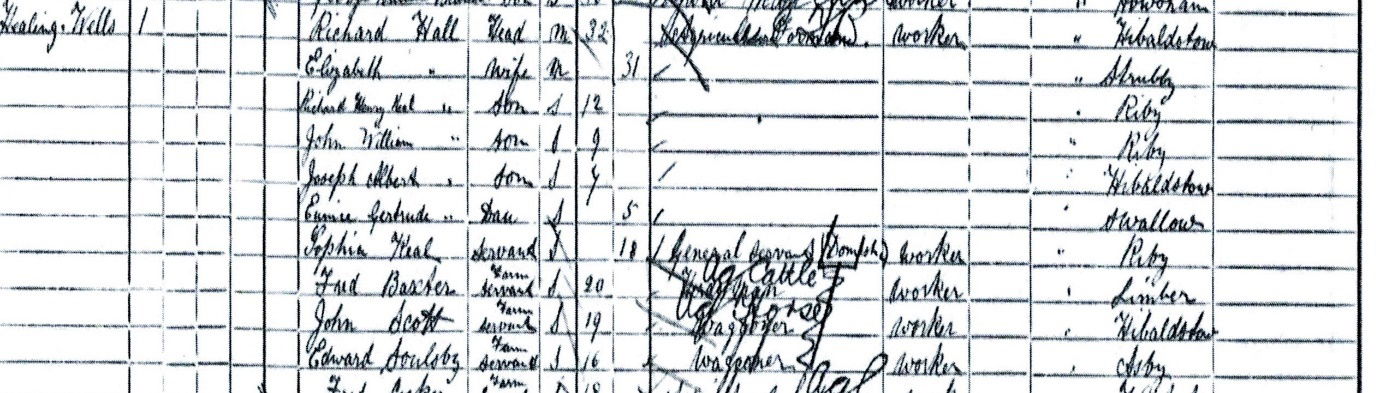

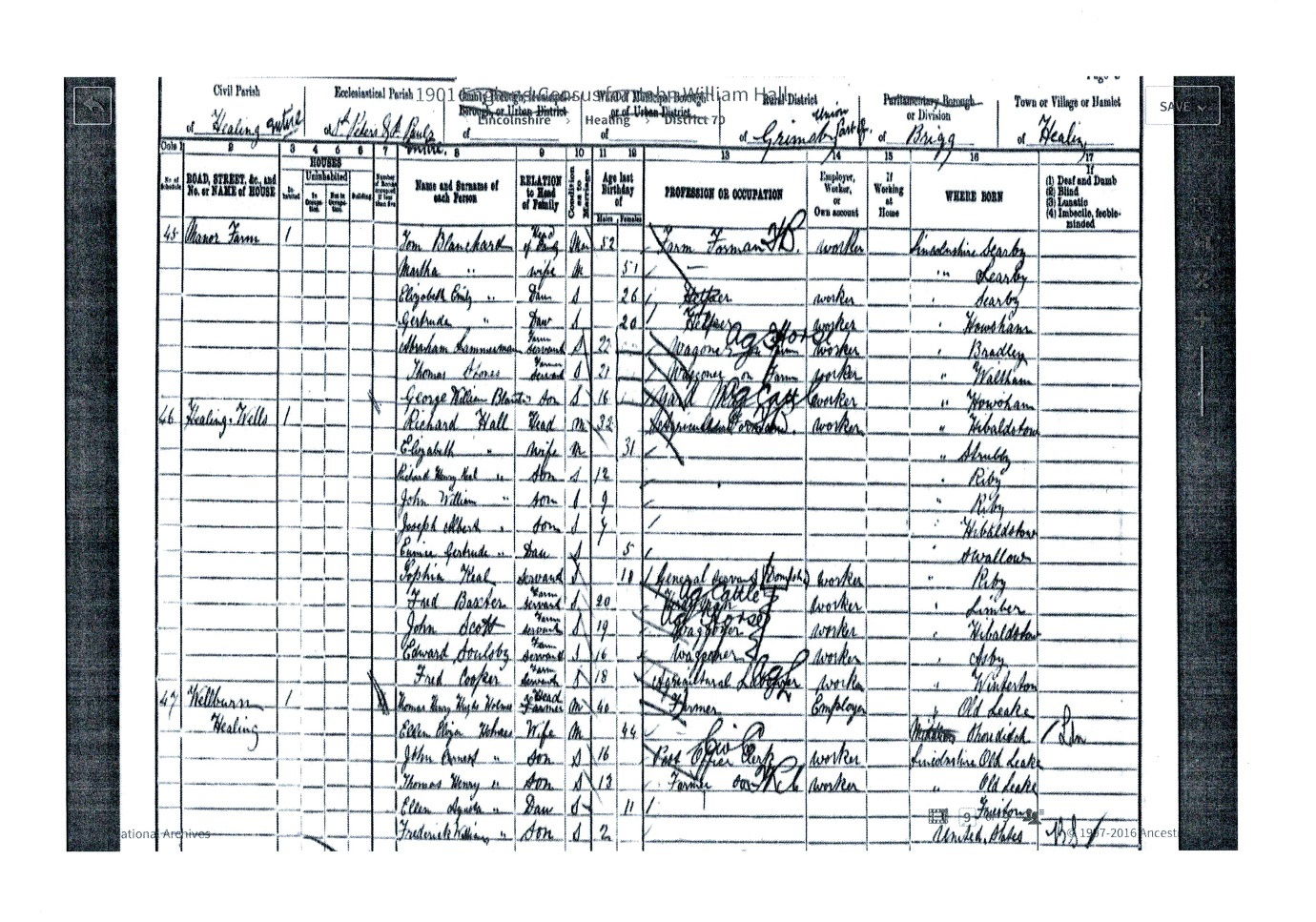

As we can see from the 1901 census which is pictured below Richard came from Hibaldstow and Elizabeth was born in Strubby which is not far from Louth. By the time this census was taken the family had grown and moved to Healing where Richard was employed as an agricultural foreman.

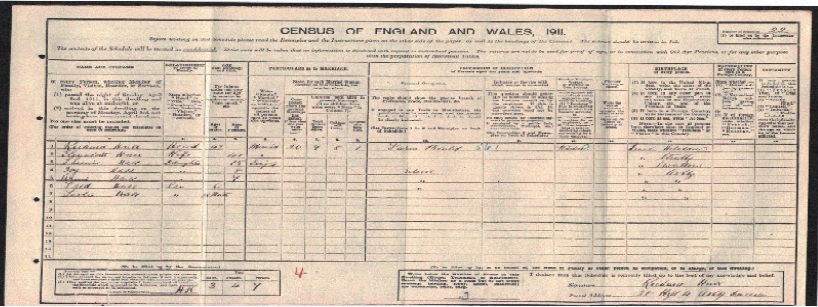

When we catch up with them again in Ashby in 1911 Richard is working as a farm bailiff. As far as we can tell they must have moved from Healing in around 1903. The census also shows that Richard and Elizabeth and their five children who were still living with them occupied 3 rooms in the house at 38 High Street Ashby which they shared with James Wrightam and his wife Emma and a young man named William Brumpton who worked as a garthman (a herdsman) on a farm.

As we can see from this last extract from the census of the same year, John William had left home and was working as wagoner on a farm which belonged to a Mr. John William Hiles of Messingham. John William continued the family tradition of agricultural labour despite the temptations of the iron works to which so many people had come to the Ashby and Scunthorpe area to seek employment.

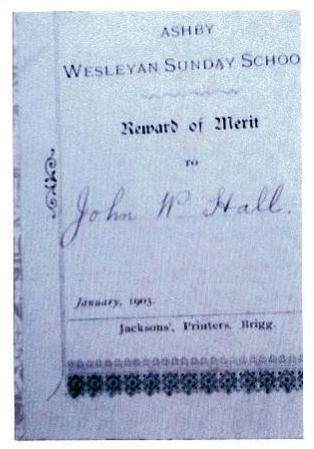

It seems fairly safe to conclude that the Hall family were members of the Methodist church or at least that Richard and Elizabeth made sure that John William attended Sunday School. The living descendants of the Hall family are fortunate to have handed down to them the Sunday School Attendance prizes given to John William in 1903 and we can see from the title of at least one of them that the subject matter of the books was suitably ‘improving’.

The surviving members of John’s family, have done much to help in the telling of John William’s story and shared many photographs and documents. Among the many heirlooms that the descendants of John William possess are family photos as well as his medals and the commemorative plaque known as the ‘dead man’s penny’ that every family received after the death of a serviceman during the war as well as his medals.

Military Service

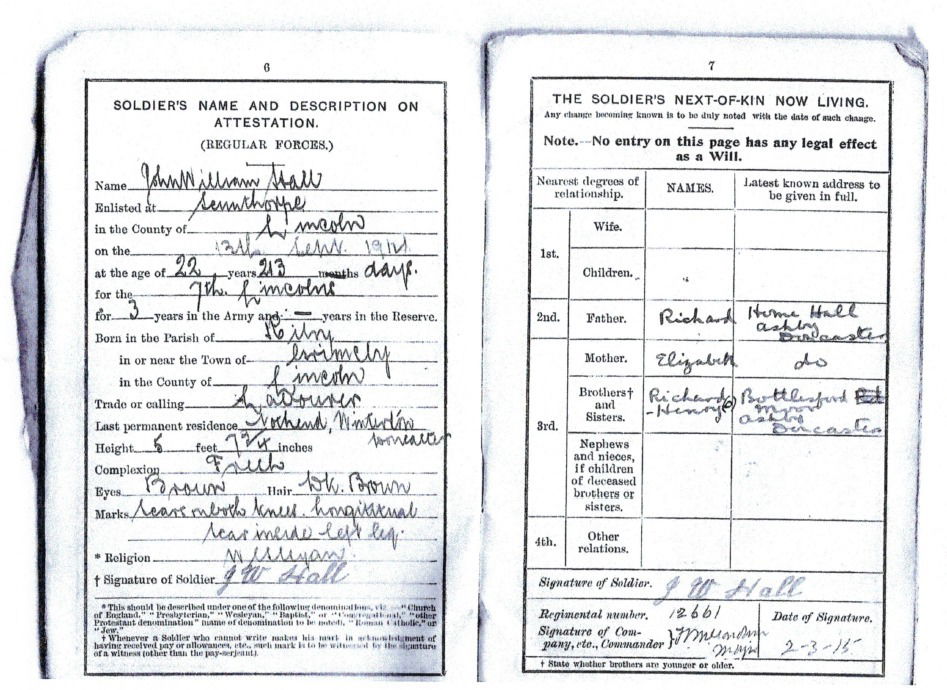

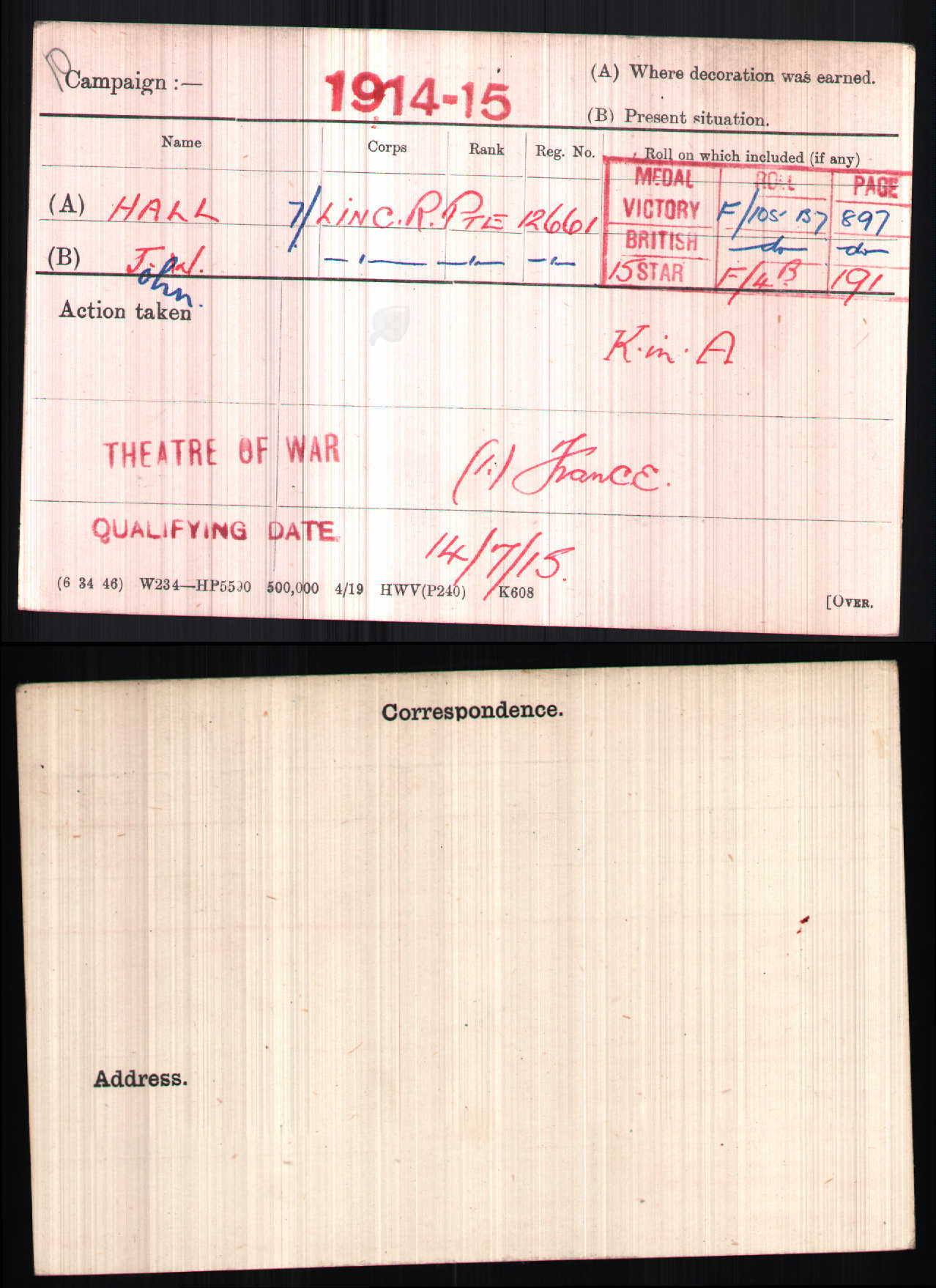

As we can see from John William’s attestation papers shown below, he enlisted into the 7th battalion of the Lincolnshire regiment on the 13th September 1914. The 7th battalion was the first of the volunteer recruits to Kitchener’s new army, the regulars and reservists having formed the core of the 1/5th Lincolns.

The fact that the right hand page of the document is filled in indicates that John William was sent on active service at some time after the 2nd of March 1915.

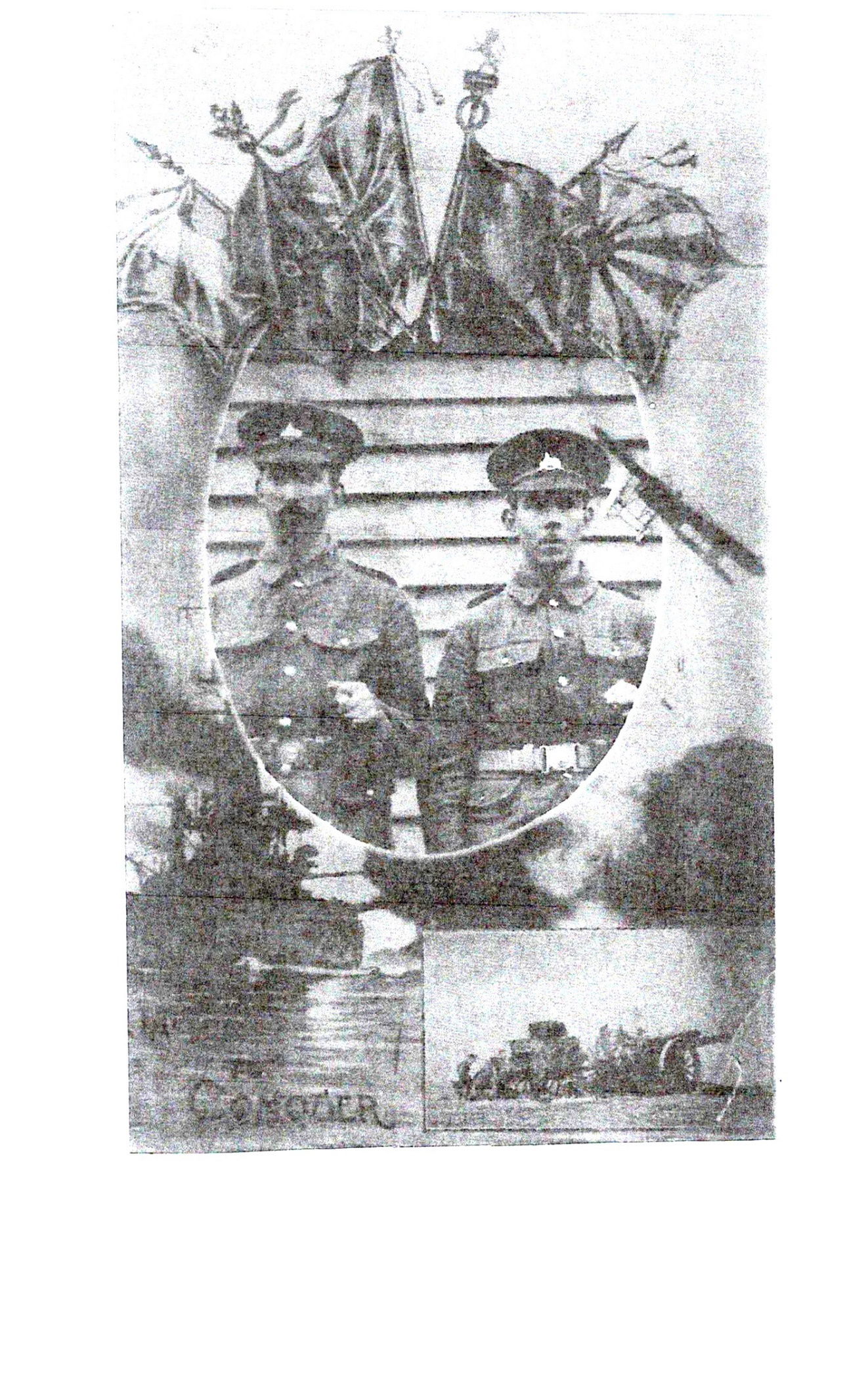

The post card photo shown below is typical of the time. It shows John William and one of his neighbours, Edwin Kendall. He was the son of Clement Kendall who was the librarian in Ashby and lived at number 50 High Street while the Hall family were living a little further down at number 38 according to the 1911 census. Perhaps John and Edwin enlisted together. His cousin Owen Kendall is one of the other soldiers commemorated on our windows and this photograph is a poignant reminder of the pain that many families in Ashby must have felt as they saw some of their young men return while they suffered the tragic loss of their loved ones.

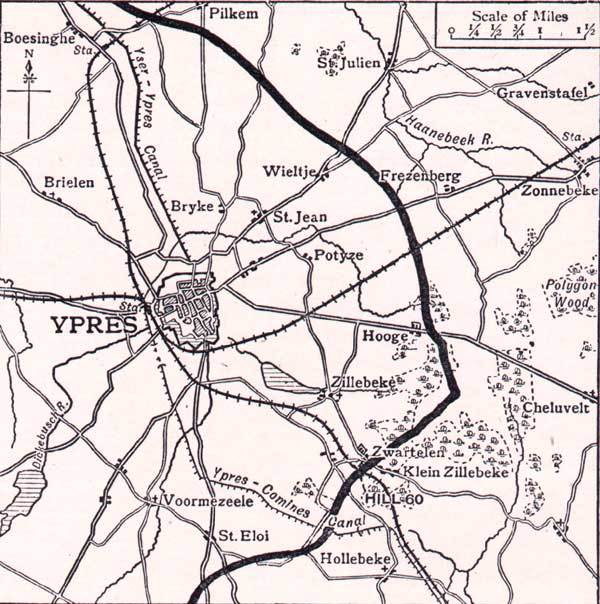

John William’s 7th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment was part of the 17th (Northern) Division which was engaged in the action in and around Ypres. They were specifically trying to capture a piece of strategic high ground which they referred to as ‘the Bluff’.

John William’s 7th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment was part of the 17th (Northern) Division which was engaged in the action in and around Ypres. They were specifically trying to capture a piece of strategic high ground which they referred to as ‘the Bluff’.

This extract from “The Long Long Trail” 1gives us an idea of what was taking place and as we can see from the maps it was not far from two well-known First World War sites, Messines Ridge and Hill 60.

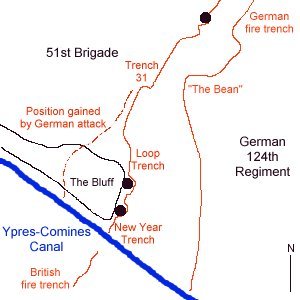

The Ypres-Comines canal, running south east from the town, cut through the front lines about 3 miles from the Cloth Hall. This was the position at the end of the First Battle of Ypres and it was much the same by 1916, the Second Battle having not altered things. Facing the British, the village of Hollebeke; on the left was the hotly-contested ground of Hill 60 and Zwarteleen, and on the right the hotspot at St Eloi. On the northern embankment of the canal, a curious mound – a spoil-heap, created when the canal was excavated – gave the British front an unusual observation advantage over the enemy. If the enemy held it, the view across the rear areas of the Salient to Hill 60, towards Ypres and down to Voormezele would have made the Salient very difficult to hold. The position just had to be held.

1 Thelonglongtrail.co.uk

The German front line fire trench lay some 200 yards ahead of this feature, which the British called the Bluff, and the Germans the Grosse, or Kanal, Bastion. British trenches ran around the forward base of the Bluff, snaking around the front of the lips of a number of mine craters that had been blown here in October and November 1915 and in January 1916. Communication trenches ran back over the Bluff itself. The canal cutting was steep sided, and over 100 yards wide. The trenches continued on the other side, with only a single plank bridge connecting the two banks.

17th (Northern) Division had moved to relieve 3rd Division in the canal sector between 5 and 8 February 1916, and placed 51st Brigade on a 1300 yard front at the Bluff position. It was also responsible for the south bank and had 52nd Brigade there. Enemy shellfire began to fall on both brigade fronts in the morning of 14 February, intensifying on the Bluff from mid afternoon. (The enemy was also shelling 24th Division at Hooge at this time). British artillery began to retaliate and the infantry at the Bluff stood by to meet an anticipated attack. All telephone wires were cut by the shelling, which severely affected the ability of units in the front line to call for support. German tunnellers blew three small mines at 5.45pm, one under the Bluff (which buried a platoon of the 10/Lancashire Fusiliers sheltering in an old tunnel) and two slightly further north, under the 10/Sherwood Foresters. Shortly afterwards, German infantry attacked between the canal bank and the Ravine. They entered and captured the front line trenches but were driven out of the support lines behind the front. Small local efforts to counter attack over the next two days failed. The all-important Bluff position had been lost, and it would take more than localised efforts to regain it.

The operations in the area of the Bluff from the start of the enemy attack to noon on 17 February cost the British 1,294 casualties.

Lieutenant-General H. Fanshawe, officer commanding V Corps, ordered 17th Division to not only recapture the Bluff but improve the position by capturing the German trench position called The Bean. He placed 76th Brigade of 3rd Division, as well as an additional RFA Brigade and an RE Field Company, under the Division for the operation. 76th and 51st Brigades began an intensive exercise in training to prepare for a frontal assault, planned to take place at dusk on 29 February 1916. All troops were equipped with the new steel helmets. 52nd Brigade held the line and carried out much preparation work, digging new communication and assembly trenches, burying telephone cables, and bringing up stocks of ammunition. This work was not helped by snowfalls, which showed up the new works to enemy observers, whose artillery promptly destroyed them. The severe weather and cold also forced a change of plan, to minimise the time that the assault troops would need to be in the front line before the attack went in. Even the date could be not be agreed: it would have to be “the second morning after the first day fine enough for artillery registration”.

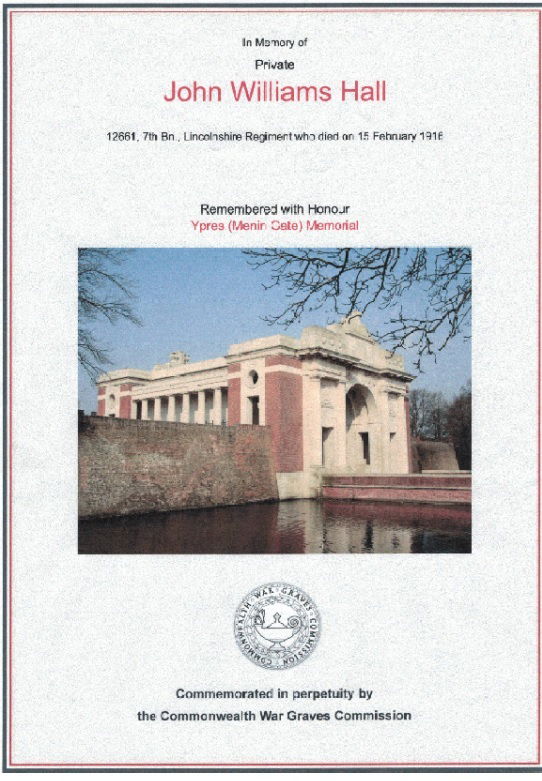

This image of John William’s medal record shows that he was killed in action and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission commemorative plaque gives the date as February 15 1916. The mistake in the spelling of his name has now been corrected and although he has no known grave his name is inscribed on Panel 21 of the Menin Gate Memorial.